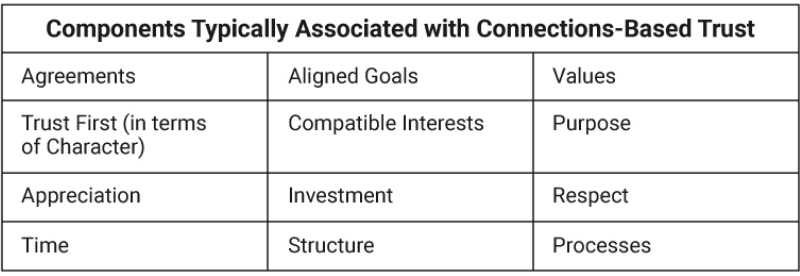

As I wrote about earlier in this series on Trust, Connections-Based Trust is all about the non-competency, non-character things that keep us connected in a healthy way.

Today’s essay is the first of a series of deeper dives into each of the three dimensions of Trust. I’m starting this tour with essays on Connections-Based Trust. I’m kicking off with this dimension because these ideas, these concepts, connect (or repel) us and make the other two forms of trust relevant (i.e., if we couldn’t stand being with each other, who cares if the other is competent or of good character?).

I’m also going with Connections first, because it’s the area where most companies not only struggle but have the biggest opportunity for gain (assuming they have a relatively well-thought-out vision, a decent product and/or service, and a big enough target market to sustain an ongoing business — I’m not a magician).

In terms of the subject of today’s essay, while all of the items in the above diagram could be categorized as culture, I purposely chose to not call the Connections dimension the “Culture-Based Trust” dimension because I prefer to separate out concepts like purpose, goals, investment and compatible interests when thinking about and measuring the health of a company culture.

According to Wikipedia:

“Culture is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities and habits of the individuals in these groups [read companies].”

[Note: No mention of purpose, goals, investment and compatible interests. I would not have included capabilities (i.e., competency) in the definition, but I totally believe culture has a huge impact on the rate of development, and even the acceptance, of capabilities.]

“Humans acquire culture through the learning processes of enculturation and socialization, which is shown by the diversity of cultures across societies.

“A cultural norm codifies acceptable conduct in society; it serves as a guideline for behavior, dress, language and demeanor in a situation, which serves as a template for expectations in a social group.

“Accepting only a monoculture in a social group can bear risks, just as a single species can wither in the face of environmental change for lack of functional responses to the change. Thus in military culture, valor is counted as a typical behavior [aka value] for an individual, and duty, honor and loyalty to the social group are counted as virtues [aka values] or functional responses in the continuum of conflict.”

I’ve come to think of culture as a soup-like thing because every culture is a unique mix of ingredients that are not all equally represented in terms of either the amount (aka weight or importance) or the impact (aka intensity of flavor).

“I’ve come to think of culture as a soup-like thing because every culture is a unique mix of ingredients…”

Just like with soup, every time you add to or remove something from the mix, the very essence of the soup changes (i.e., the look, taste, feel and even it’s level of healthiness). Too much of this, or not enough of that, or any of this other stuff, will make it all wrong. It’s the exact same dynamic associated with building a great company culture.

To make things even more complicated (maybe even maddening), this “soup” is always created by a collection of “chefs” and “sous chefs” who are not all in the kitchen at the same time watching one another as the soup is created. Ugh, right?

The result of all of the above is that, especially when it comes to company cultures:

- Some cultures have been very purposely built, while other cultures have been randomly built.

- Some cultures are relatively simple — purposely composed of just a handful of ingredients (e.g., core values). Some are a bit more complicated, and some cultures are more complex, comprised of a lot of ingredients, some of which are dumped in heavily, others modestly, others sprinkled in ever so lightly.

- Most cultures have a few ingredients that were either accidentally or secretively added.

- Some cultures are healthy, other cultures are becoming spoiled, and some are poisonous (i.e., toxic).

- Cultures are living things that evolve over time and, as such, constantly need to be tended to (i.e., building and keeping a high trust culture is a never-ending thing).

- Some cultures will appeal to our sense of taste, and others we will find unpleasant and some revolting.

- The leader of leaders in every group owns their group’s culture.

In my experience, one of the toughest things about building a great high trust company is creating a culture that:

- You and virtually all of your employees love

- Attracts the kind of talent you not only need but with whom you want to be connected

- Repels the people who don’t like your unique collection of ingredients because those are the people who will try to reformulate, if not poison, your soup

- Is conducive for building an extraordinarily productive, humane and resilient company (i.e., a company that is built to last — you do want that right?).

As you would expect in this day and age, there has been a tremendous amount of research on culture across all sorts of group types, including countries, regions, tribes, communities and even companies. Some of the most notable names in the various fields of study associated with culture include Kluckhohn, Strodtbeck, Hofstede and Edward T. Hall.

The work of Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck was oriented around the big idea that every culture faces the same basic survival needs and must answer the same universal concerns about:

- Human nature;

- The relationship between human beings and the natural world;

- Time;

- Human activity, and

- Social relations.

Hofstede, sometimes called the father of modern cross-cultural science and thinking, identified these five key value dimensions:

- Power distance (aka hierarchy);

- Individualism;

- Masculinity;

- Uncertainty avoidance, and

- Time.

Kluckhohn, Strodtbeck, Hofstede and Hall each identified one’s perception of time as one of the major ingredients in every culture.

Hall in particular is credited with introducing several useful frameworks for helping us better understand culture, not the least of which is what is now called “chronemics,” the study of how our perception of time influences a broad array of both social norms (e.g., punctuality, deference, and one’s willingness to wait), as well as our individual life view (e.g., longer-term focused versus living in the moment; working on one thing versus lots of things at a time, and more).

Over the coming weeks, I’m going to go deeper into a number of the categories associated with Culture that I believe are helpful to understand the art and science associated with building a high trust company.

These dimensions include:

- Values;

- Individualism vs. collectivism;

- Hierarchies, and

- Time.

At the risk of stating the obvious, these four dimensions — and there are even more — are not independent but mixed together like a soup whose taste, texture, strength and beauty is entirely due to its interdependent and complex structure. To make culture even more maddening, these ingredients are living things that constantly evolve; just like we do as humans (future essay). Whether we are mindful of this complexity or not, it is there.

IMO, sooner or later you’ll want to understand this thing called Culture if you genuinely want to comprehend how and why people think and act as they do, so that over time you become a more thoughtful and capable leader…

If we want to not only lead but build something that endures, I’m not sure you have any choice but to follow me (or someone else you trust) down these rabbit holes associated with Culture. IMO, sooner or later you’ll want to understand this thing called Culture if you genuinely want to comprehend how and why people think and act as they do, so that over time you become a more thoughtful and capable leader, chef or sous chef.

Executive Summary

- Connection-Based Trust is all about the non-competency, non-character things that keep us connected to others in a healthy way. Yet this is the area where most companies struggle. As a result, it’s the area where most companies have the biggest opportunity for gain.

- Every culture might be compared to a soup, composed of a unique collection of ingredients, which are not all equally represented in terms of either the amount (aka weight or importance) or the impact (aka intensity of flavor). As such, cultures are created by a collection of chefs and sous chefs who are not all in the kitchen at the same time or watching one another as the soup gets made.

- Creating the expected culture is one of the toughest things when building a great high trust company (HTC). The four dimensions (mixed together like ingredients of a soup, interdependent and complex in structure) include: values; individualism vs. collectivism; hierarchies, and time. The leader of leaders in every group owns their group’s culture.