In Essay #1 on Work, I presented the case that only through Work (with a capital W — meaning work we love) can we hope to achieve self-esteem and thereafter, if we are fortunate, self-actualization.

In Essay #2, I submitted the case that Work, like each one of us, is a very unique and individualized thing. That Work for me is very different from Work for you. I know it may appear trite and cliché, but the fact is each of us is a unique and evolving social being composed of a kaleidoscope of needs, interests, talents, relationships, values, experiences, skills, goals, aspirations and motivations.

In this essay, I’m introducing an entrepreneur’s / coach’s (aka a simpleton’s) overview of why we Humans are the way we are and why leaders, young and old, need to focus on a few very core things if they want to build great teams and great organizations (aka tribes).

According to a lot of scientists, if we were to hop on board a time machine (you have one of those right?) and go back about 100,000 years, we’d arrive at a moment in history where, in addition to Homo Sapiens, there were another six to eleven other human-like species (collectively referred to as hominoids), each with relatively long histories and developed cultures.

Get back in our time machine and travel forward to about 10,000 years ago (a short 3,000 or so years after the end of the Ice Age) and we’ll find that our species (i.e., Sapiens) is the only human species remaining. What happened during those 90,000 years is debatable (what isn’t these days?) but there appears to be a relatively broad consensus that Sapiens prevailed because they (that is, we) were the “humans” with the most socially evolved brains.

Human Developmental Needs

Every living thing (e.g., birds, plants, hippos, humans, etc.) has needs. Truth is, some needs are apparent, and some needs are not so apparent (even to us).

Furthermore, some of these needs are must-haves (e.g., food, water and sleep), some of them are associated with more complex life forms (e.g., mammals versus plants), and some are great to have but not necessary for survival (e.g., self-actualization).

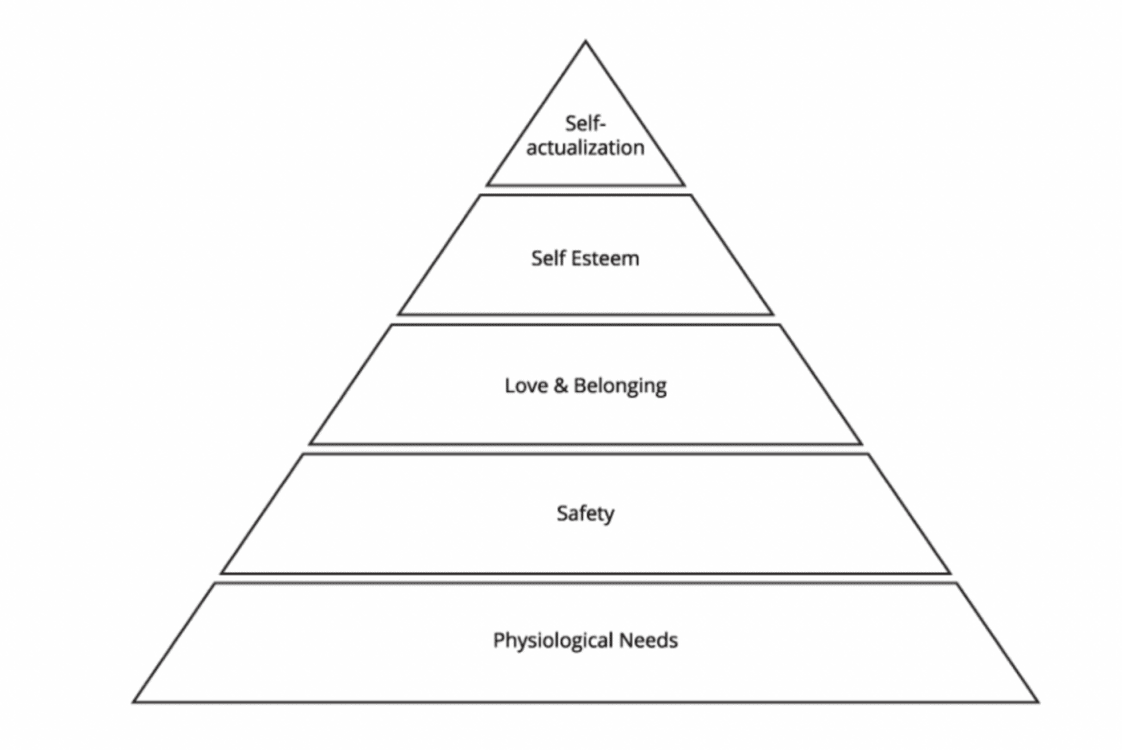

Abraham Maslow, an American psychologist, created a simple model (he actually didn’t use the pyramid but that’s a tale for another essay) — Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs — to help us not only understand the hierarchy of our (human) needs (which we will collectively refer to as “Needs”, or singularly as a “Need”) but a hierarchy for understanding human motivation (he coined the term meta-motivations).

At the crux of Maslow’s model is the notion that the bottom of the pyramid contains our most basic Needs and that our Needs move from “must-have” to “need-to-have” to “like-to-have” to “I’ve-got-all-I-need-but-I-want-to-be-more” as we move higher and higher up the pyramid.

While Maslow originally believed each level must be satiated before a person could move to the next level, he later came to believe that the human (i.e., Sapiens) brain is a complex system comprising a host of parallel processes running simultaneously, and that the human condition is comprised of an array of different (oftentimes competing, if not conflicting) motivations emanating from various levels of the hierarchy. Consequently, Maslow purposely used terms such as “relative,” “general,” and “primarily.”

At the risk of stating the obvious, each of us has to take personal responsibility for seeing that our basic needs, or “Base Needs” (as in foundational), are being met. It is simply impossible for us to become a self-actualized being if we don’t take personal responsibility for not only meeting our current Base Needs but our future Base Needs as well.

In essence, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs provides an exceptional tool for helping us humans prioritize the development of our well-being (assuming we’re interested in becoming self-actualized).

So… what does Maslow’s Hierarchy have to do with Work and companies? Glad you asked.

Humans as Social Creatures

As you may recall, about 10,000 years ago, our species was the only remaining member of hominoids on the planet. Even though scientists (especially social scientists) seem inclined to argue about almost everything, the general consensus is that we (i.e., Sapiens) prevailed because we had the most socially evolved brains.

So, what is it about the Sapiens brain that makes us more social? And why is the founder of Ninety.io even writing about evolution?

Think about what life was like 50,000 years ago or, heck, even 3,000 years ago!

Here we are, pretty much naked, and we need to figure out whether or not to trust someone (I’ll get much deeper into this in a future essay). On the one hand, that other human could kill us. On the other, they could help us acquire food, protect our family, help us build a structure to not only protect us from the elements, but store and protect our food. Maybe they could even teach us something, maybe do the stuff we don’t either like doing and /or stink at doing, and, heck, even make us laugh.

Humans as Trusting Creatures

So how did we come to trust other humans?

Current research (including Paul Zak’s great book, Trust Factor) makes a compelling case that when it comes to trust, while there are many things that differentiate our brains from other animals, one of the key factors is a neurotransmitter called oxytocin, a hormone that is sometimes referred to as the “cuddle hormone” or the “love hormone.” In short, oxytocin helps us assess whether we should run from or approach and interact with (i.e., trust) another human being.

While there are several theories, I subscribe to the notion that the Sapiens’ socially evolved, oxytocin-enhanced brain helped these particular hominoids team up to procure food and defend themselves, thus satisfying the first two levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy — primary Level 1 Need being food, water and sleep, and primary Level 2 Need being security.

Humans as Tribal Creatures

Over time, our socially evolving ancestors began to see the power associated with trust. More specifically, they learned that if they didn’t trust first, there was no way they could divide and conquer in order to take advantage of their individual talents. Dividing and conquering not only made belonging (i.e., being with others) more valuable (a primary Level 3 Need), but in turn, it helped them to become more self-aware (i.e., where their individual talents lie versus those of their fellow tribe members). It also helped them develop their primary Level 4 Need, which is self-esteem (i.e., they not only belonged, but felt that they were contributing to the well-being of their tribe — that they mattered).

What Came First: Words or Emotions?

More than 100,000 years ago, our ancestors started to develop several powerful capabilities. The first was likely an increasing array of emotions, followed by words. Words became one of the earliest super tools. Words helped them not just label things (e.g., good to eat, bad to eat), but, when connected, gave them the ability to create more and more sophisticated ways of understanding themselves, others and life.

In terms of emotions, it’s likely that our earliest were those that helped us with just basic survival (e.g., fear and love). In time, as belonging became more and more important, these emotions became more sophisticated (e.g., shame versus guilt). Once our emotions became more and more sophisticated (e.g., rage versus anxiety), we started to develop words, and sentences, that initially helped us better understand and communicate what we were feeling (e.g., anxious versus melancholy). The words themselves likely helped put us on the path toward greater competencies that led us to become these beings with the Need to self-actualize.

The Power of Purpose

Fast forward a bit more and we start to see our oxytocin-enhanced forbearers and their tribes starting to develop a sense of purpose that not only drove the individuals, and bound tribes more tightly together, but drove their actions. Sometimes these purposes were simply to make life better for themselves or to defend their way of life. Other times they were to pursue some envisioned greater sense of being and/or glory (e.g., “the greater glory of Rome”).

Hierarchies of Competency

In time, as Sapiens pursued purpose and developed even more complex ways of thinking about, talking about and understanding life, humans began to excel — not just at dividing and conquering based upon an array of talents and competencies (e.g., talent, skills, experiences and energy) — but at envisioning greater futures and delegating and elevating. This included getting others to help so they could focus on bigger, better and / or or more challenging opportunities (an essay on “Flow” is also coming soon).

It also meant forming hierarchies of competencies, like organizational building, planning (time and process) and leadership skills. All of this made life safer and richer, not only that day, but for what was then tomorrow and beyond.

These hierarchies of competencies (e.g., planning, process, leadership, management, politics) enabled Sapiens to build larger and larger tribes for a host of purposes, including security and enhancing their ability to create things (i.e., “to make life better”) that required larger and larger groups of people (e.g., building the Great Pyramids).

Hierarchies of Values

As Sapiens built larger tribes to keep things “civil” (i.e., to get along), they began to create hierarchies of values that codified acceptable and unacceptable behaviors. Initially, these values were oftentimes codified in the form of what we think of as religious teachings and principles (which appear to date back at least 5,000 years ago).

Values made it easier for humans to not only work together but, in particular, as the size of their tribes grew, values helped hold them together. [For example, one of the reasons it appears marriage and monogamy became widespread was that there was far less stability (e.g., more murders) in tribes that had large-scale polygamy. Yes, one can imagine how young men might become very uncivilized when all of their prospective female mates are hoarded by other “more desirable” or more powerful men.]

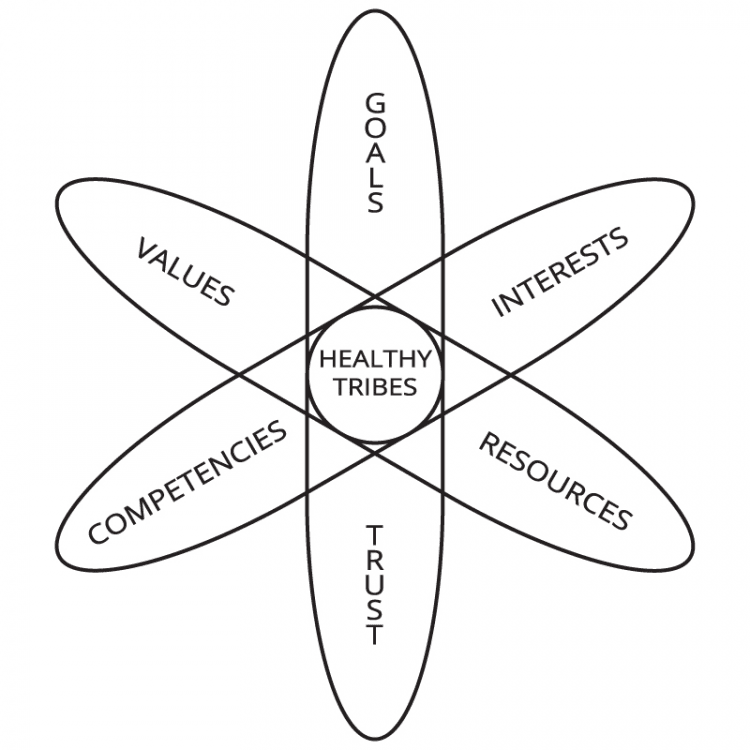

Healthy tribes (i.e., organizations) are led by people who not only respect our values and the fact that we are bound together by complementary interests, talents and goals, but possess the ability to think longer term, so that the tribes and their people are capable of making life better for themselves and those around them.

Norms, Laws and Rights

In time, general values (e.g., honesty, which is core for trust) turned into social norms, which are much more specific standards, rules, guides and expectations for actual behavior (versus values which tend to be more abstract conceptions of what is important and worthwhile).

At some point, Sapiens started to enact laws and regulations that essentially decreed certain norms so important that there would be penalties associated with their violation.

Finally, during the last couple thousand or so years, humans started to talk about “rights.” The founders of the United States of America believed humans had certain “unalienable” rights. While they found these to be “self-evident,” it appears this wasn’t the case because ultimately, they created something called the Bill of Rights to help enumerate the constitutional rights of U.S. citizens (as did the United Nations with The Universal Declaration of Human Rights [UDHR], which was published in 1948 shortly after, and in response to, World War II).

I believe — and both the Bill of Rights and the UDHR are consistent with this belief — that a human’s unalienable (aka inalienable) rights include the right to:

- Breath (Maslow Level 1, or “ML1”)

- Eat (ML 1)

- Sleep (ML 1)

- Move (ML 2)

- Think (ML 1–5)

- Talk (ML 3–5)

- Associate (ML 3–5)

- Create (and procreate) (ML 2–5)

- Learn (ML 4–5)

- Own the things we create or trade them for things owned by others (ML 4–5)

- Defend our rights. (ML 1–5)

In my opinion, it is only through having these unalienable rights that we are truly able to thrive and flourish as human beings.

I also believe that what we think of as Rights has evolved a lot over the years. As an example, the UDHR includes not just unalienable Rights but also foundational Rights (i.e., those needed to protect our unalienable rights) and even aspirational Rights (e.g., wouldn’t it be great if everyone who wanted a job had one). A separate essay on these three types of Rights is in the “Works” (yes, pun intended).

Rights versus Needs

I believe Needs are not Rights. Needs are extraordinarily real, but to state the obvious, when born, we are totally incapable of meeting our individual Needs. For a host of reasons, not the least of which is that each of us is extraordinarily unique, it is impossible for a human to self-actualize without becoming someone who takes ownership for his or her Needs (i.e., you guessed it — to embrace Work). Otherwise, it will be impossible to achieve self-esteem, let alone self-actualize, since we would be dependent upon someone or something else such as an individual or a group or both.

One final note on Needs versus Rights: I deeply appreciate that not every person is fully capable of being able to take care of his or her Needs. This is where the tribe and its values, laws and regulations come into play. Consequently, we believe healthy tribes endeavor to take care of those members who have either temporarily fallen on hard times, or worse, are incapable of taking care of themselves.

In short, I believe healthy tribes (e.g., teams, companies, countries) have shared values and complementary interests, talents and goals.

In short, I believe healthy tribes (e.g., teams, companies, countries) have shared values and complementary interests, talents and goals. I further believe that healthy beings and tribes need to be led by people with the ability to not only respect and nurture what holds the tribe together but think longer term, so that the tribes and their people are adequately prepared for today, tomorrow and beyond (that especially includes being prepared for hard times like now). Said another way, I believe Maslow’s Hierarchy not only applies to individuals but to tribes (e.g., groups, companies, communities, states, countries) as well.

Executive Summary

- Sapiens’ socially evolved brain helped them team up to find food and defend themselves, better satisfying the lower-level Needs of Maslow’s Hierarchy as a group.

- Our ancestors found security, self-esteem and opportunity in trust. They learned that if they didn’t trust, there was no way they could organize as a tribe and take advantage of each person’s individual talents and thrive.

- Words became one of our earliest super tools.

- Emotions initially helped us with basic survival, and as the Need for belonging became more and more important, emotions became more sophisticated (e.g., shame versus guilt) and helped us evolve.

- A sense of purpose not only bound tribes more tightly together, it also drove their actions.

- Hierarchies of competencies allowed Sapiens to build larger tribes, working together to make life better. Competencies included leadership and team-building skills, getting others to help so they could focus on bigger / better opportunities.

- Values made it easier for humans to work together. As the size of the tribes grew, values helped hold them together.

- Values turned into norms. Norms became laws and regulations, with penalties associated with their violation.

- Healthy tribes (i.e., organizations) are led by people who not only respect our values and need to matter (i.e., have purpose), the fact that we are bound together by complementary interests, talents and goals, but possess the ability to think longer term, so that the tribes and their people are capable of making life better for themselves and those around them.